1. Introduction: A Quiet Crisis in the Heart of Europe

For centuries, the idea of a home has been central to European life. It was never just a place to sleep—it was security, identity, stability. Whether a modest apartment or a small house with a garden, having a place to call one’s own was part of what defined a good life.

But today, across Europe, this quiet cornerstone is crumbling.

Rents are rising at record pace. Property prices soar far beyond the reach of working families. Young adults, even those with stable jobs, are unable to afford a first home. And millions of long-time tenants are being forced out of their neighborhoods—not because they failed to pay, but because the building is being “renovated” for someone else, someone who can pay more.

This crisis is not marked by riots or breaking news alerts. It unfolds in silence—one notice, one eviction, one failed mortgage application at a time. The victims don’t shout; they pack boxes, they move away, they disappear from statistics and streets alike.

What’s collapsing is not just access to housing. It’s the very promise of stability that European societies were built upon. And unlike past housing crises triggered by war or disaster, this one is systemic. It’s embedded in financial structures, tax codes, and market logics that favor speculation over shelter, profit over people.

While politicians debate reforms and central banks tweak interest rates, the human cost grows: families torn from communities, young people postponing families, elderly residents forced into uncertainty in their final years.

This article is a call to pay attention.

We must name the quiet collapse before it becomes irreversible. And we must ask ourselves what kind of Europe we are building—one of concrete and profit, or one where people can still live, grow old, and belong.

2. Forced Out: The Hidden Wave of Tenant Displacement

Renovation as a weapon: When “modernization” means eviction

In cities across Europe, scaffolding has become a symbol not of renewal, but of quiet exile.

What appears to be progress—fresh paint, new balconies, better insulation—is often a coded message: You are no longer wanted here.

Under the banner of “modernization”, countless landlords are exploiting legal loopholes to force tenants out. The method is subtle: announce extensive renovations, declare the building temporarily uninhabitable, and raise rents beyond affordability once the work is done. Sometimes the improvements are real. Sometimes they are cosmetic. But the result is the same: longtime residents are pushed out, and the building is repopulated with those who can pay twice as much.

This process has a name in some countries: renoviction. But in many others, it remains unspoken, undocumented, even legal. Elderly tenants, families with children, disabled individuals—those who built lives in these homes—are told to leave under the pretense of improvement. Many never return.

It’s not about bad landlords. It’s about a system that rewards eviction more than stability. Real estate investment funds, private equity firms, and pension capital increasingly treat homes not as places to live, but as speculative assets. The more you can “upgrade” the tenant profile, the better the return.

And because this process doesn’t leave burned-out buildings or media scandals, it escapes political attention. There are no headlines for people who leave quietly.

But the damage is deep. Communities unravel. Schools lose children. Elderly residents lose their lifelines. And cities lose their soul—bit by bit, flat by flat, block by block.

This isn’t modernization. It’s systemic displacement dressed in respectable language. And unless we name it for what it is, it will reshape our cities in silence—until nothing remains but profit.

Legal loopholes and weak protections for renters

For millions of European renters, the law no longer feels like a shield—it feels like a sieve.

Tenant rights exist on paper, but in practice, they are riddled with holes wide enough to drive entire real estate empires through. Whether it’s loopholes that allow unjustified evictions during renovations, or quiet legislative shifts that weaken rent controls, the effect is the same: insecurity.

In many countries, laws intended to protect tenants have not kept pace with the financialization of housing. What once was a relationship between landlord and tenant has become a battlefield between private individuals and anonymous investment firms. Legal frameworks designed for small-scale ownership now struggle to regulate corporate actors who exploit every grey zone with surgical precision.

Some of the most common tactics include:

- Use of “temporary” contracts to deny long-term tenancy rights.

- Strategic “modernizations” to justify rent hikes or eviction.

- Conversion of rental housing into luxury condominiums, leaving renters without alternatives.

- Pressure to accept buyouts far below market value, with no legal obligation to rehouse displaced families.

Even when protections exist, tenants often lack the resources, time, or knowledge to enforce them. Legal aid is scarce. Court cases take years. By the time justice arrives, the home is already gone.

In countries like Germany, France, or the Netherlands, strong tenant movements have pushed for reforms. But even there, loopholes remain—and enforcement is weak. In Southern and Eastern Europe, the situation is often worse: fragmented laws, little oversight, and a cultural stigma that sees renters as second-class citizens.

This isn’t just a legal failure. It’s a structural imbalance of power. One side has lawyers, lobbyists, and capital. The other has a lease and the hope that they won’t be next.

As long as the law remains so easy to bypass, rental protection is a myth. And myths, no matter how comforting, do not keep roofs over people’s heads.

Rising rents, shrinking rights

Across Europe, the cost of living in a home has quietly decoupled from the right to do so in dignity.

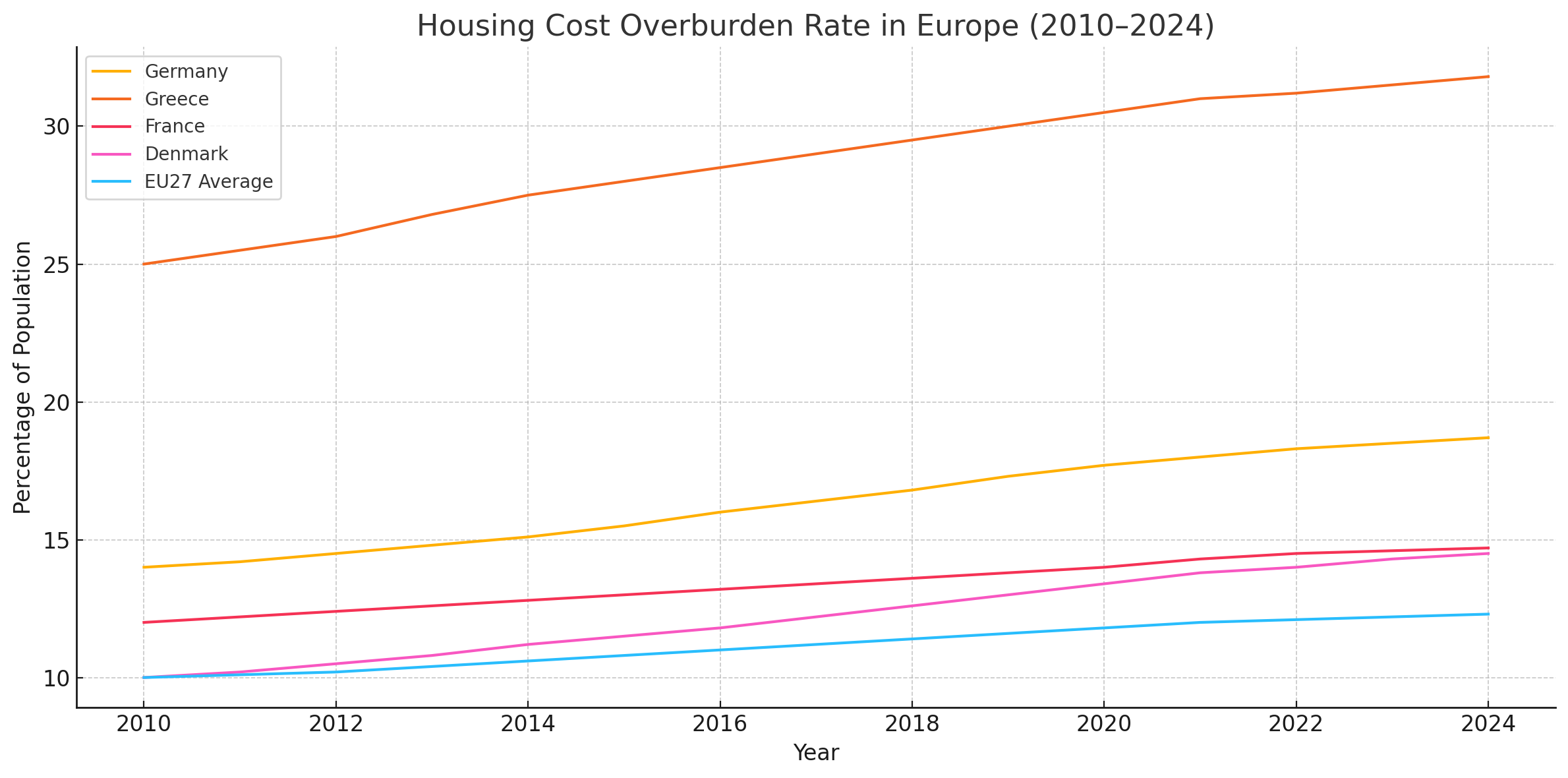

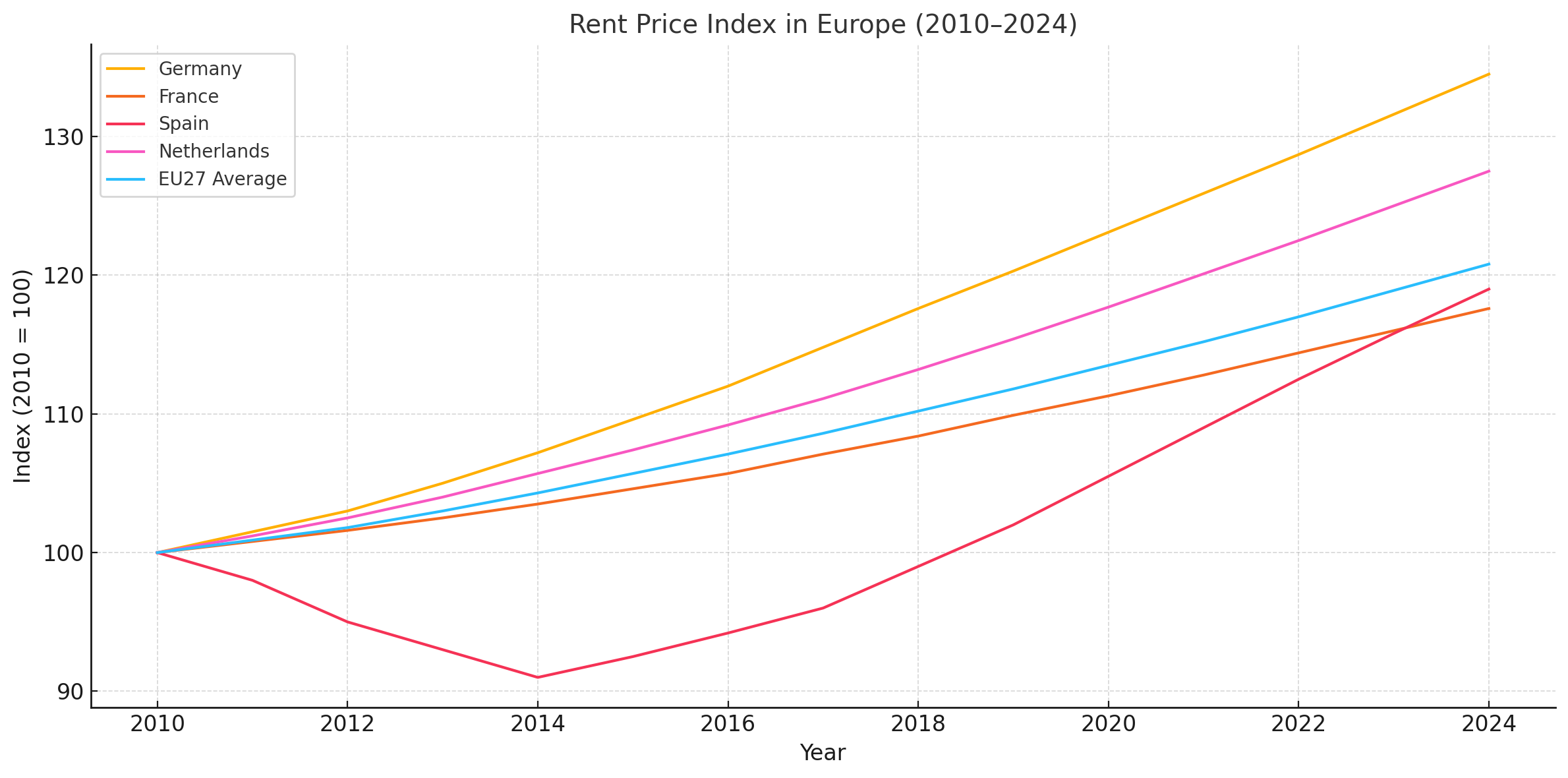

In cities from Lisbon to Berlin, from Prague to Paris, rents have soared beyond what most working families can afford. While wages stagnate or barely rise, rental prices have entered a speculative spiral—driven not by supply and demand in any traditional sense, but by global investment strategies targeting housing as a “safe asset.”

For the average tenant, this has created a double bind:

They pay more than ever before, yet feel less secure in their homes than ever before.

In the past, a long-term rental agreement offered a sense of stability. Today, tenants sign contracts with one eye on the fine print and the other on the calendar, wondering how long until the next increase—or the next notice to leave.

What makes the situation worse is the simultaneous erosion of renters’ rights. Rent caps are weakened or lifted. Legal protections are watered down. Even simple mechanisms—like limiting how often rent can be raised—are being dismantled in the name of “flexibility” and “market efficiency.”

In many cases:

- Rent increases vastly outpace inflation and wage growth.

- Families are forced to relocate every few years, disrupting work, schooling, and social ties.

- Essential workers—nurses, teachers, delivery drivers—are priced out of the cities they serve.

- Young people are trapped in shared flats well into their thirties, unable to afford a place of their own.

And yet, the public debate often frames renters as “temporary” or “less invested,” overlooking the millions of citizens who will never own property and who nonetheless form the social and economic backbone of Europe.

The result is a housing system that is increasingly transactional, extractive, and volatile. In such a system, rights become privileges—and those privileges are priced out of reach.

This is not just a failure of policy. It is a quiet dismantling of one of the core promises of European democracy: that a stable, decent home should not be a luxury, but a human right.

Who profits from the purge? Investors over inhabitants

Behind every forced move, every rent spike, every “renovation notice” delivered with legal precision, there is often an answer to a silent question: Who gains from this?

The answer is rarely the people who live in these homes.

Across Europe, homes have been transformed from places of life into instruments of profit. Private equity firms, real estate funds, and multinational investment groups are buying up entire buildings—not to maintain communities, but to maximize return on investment.

These groups operate under a simple logic:

Extract more value from each square meter, as quickly as possible.

That means:

- Pushing out long-time tenants who pay lower legacy rents.

- Renovating only to justify sharp increases or convert units to luxury flats.

- Exploiting legal loopholes to sidestep rent controls and tenant protections.

- Letting properties sit vacant while their market value appreciates.

In many cities, the largest landlords are no longer individuals or even local companies, but institutional players with no ties to the neighborhood. Their decisions are made in distant boardrooms, guided by quarterly returns—not by the lives unfolding behind the doors.

The economic outcome is staggering:

- Real estate speculation drives housing prices far beyond local income levels.

- Wealth concentrates in fewer hands while social cohesion collapses.

- Entire districts are rebranded and repackaged to suit investors’ portfolios, not residents’ needs.

What’s worse is that these dynamics are often facilitated by public policy.

Governments eager to attract foreign investment sell housing assets, deregulate markets, or offer tax incentives—believing that development equals progress. But when this development displaces the very people it claims to serve, the result is not renewal, but quiet erasure.

This is not a marginal issue.

It is a systemic redirection of value—from the many who live and work, to the few who speculate and own.

To reverse it, we must first name it: The purge of the poor is profitable. And unless it is checked, it will continue—not as a glitch in the system, but as its intended function.

3. The End of the Ownership Dream

A house with a garden? No longer realistic for most

There was a time when owning a modest house with a garden was a reachable goal for large parts of the European middle class. It was not seen as a luxury, but as a life milestone: the reward for decades of work, a safe place to raise children, a form of old-age security.

Today, that dream is slipping away — not because people desire less, but because the system gives them less for more.

Across Europe, housing prices have surged far beyond wage growth. In many countries, home ownership now requires not only two full-time incomes, but also a substantial inheritance or family backing — something many younger generations simply don’t have.

Even in rural areas once known for affordability, speculative investments and second homes have driven up prices. In cities, the situation is even more dire:

- Entry-level apartments cost up to 15 times the average annual salary.

- Banks demand higher down payments and stricter creditworthiness.

- Interest rates fluctuate unpredictably, making long-term planning nearly impossible.

For many, the result is resignation:

“We will rent for life, and we will be grateful if we can even do that.”

This resignation is not just economic — it’s psychological and social.

It changes how people imagine their future, how they start families, how they feel about stability and agency. A whole generation grows up with the knowledge that they are locked out of what their parents considered normal.

This is not progress.

It is a regression hidden behind economic jargon and urban development plans. A society that denies most people the ability to root themselves is not a healthy one. And a system that treats housing as a commodity instead of a right will not produce stable lives — only rising inequality and quiet despair.

Wages stagnant, prices skyrocketing – a losing race

While property prices and rental costs have soared, wages have barely moved. For millions of people across Europe, this has created a silent economic trap: the harder they work, the further behind they fall.

Inflation, especially in the housing sector, has outpaced wage growth for over a decade. In some regions, real wages — adjusted for inflation — have even declined. Meanwhile, construction costs, land prices, and demand from high-income investors continue to rise. The gap between what people earn and what a home costs is no longer a step — it’s a chasm.

This isn’t just a problem of poverty — it affects the heart of the middle class:

- Nurses, teachers, skilled workers — once symbols of social stability — now struggle to find adequate housing in the areas they serve.

- Young professionals with degrees and steady jobs are locked out of ownership despite doing “everything right”.

- Families spend 40% to 60% of their income on rent alone, leaving little room for savings, emergencies, or investment in their future.

It is a race without a finish line, where each month feels like treading water while the current gets stronger.

And behind these numbers lies something deeper: a growing sense of powerlessness. People don’t just feel financially strained — they feel betrayed.

Betrayed by a system that promised effort would be rewarded, stability would be earned, and the dream of a home would remain within reach.

But the truth is now undeniable:

“The cost of living has outgrown the value of labor.”

Unless this race is stopped — or reversed — entire generations will live without ever finding footing, drifting through rented lives in someone else’s investment portfolio.

Down payments, interest rates, and impossible entry barriers

The dream of buying a home begins — and often ends — with the down payment.

For most young adults and middle-income families, the first hurdle is already insurmountable. In many European cities, down payments now require tens of thousands of euros, often the equivalent of 5 to 10 years of disciplined saving — assuming no major life events, setbacks, or children along the way.

And then, there’s the second blow: interest rates.

After years of ultra-low borrowing costs, the recent rise in interest rates has hit aspiring homeowners with brutal force. A mortgage that once looked manageable now demands hundreds more per month, turning borderline affordability into sheer impossibility.

Even worse, many banks now demand:

- Higher equity percentages from first-time buyers,

- Stricter credit histories,

- And dual incomes — effectively locking out single parents, freelancers, and those in less stable but essential professions.

The result? A generation that doesn’t even get to try.

This isn’t just an issue of financial arithmetic — it’s a systemic trap:

- The longer people rent, the less they can save.

- The less they save, the longer they rent.

It’s a loop designed to keep ownership out of reach — not by accident, but by the structure of the market itself. And while the gate remains locked, prices continue to rise beyond the fence.

For many, the idea of owning a home has shifted from “life goal” to distant fantasy.

What was once a foundational step in building a future is now a barrier to hope.

Competing with investors and corporate landlords

Buying a home today doesn’t just mean facing high prices and tough loan conditions — it means competing with giants.

In many regions across Europe, private individuals are no longer the dominant force in the housing market. Investors, corporate landlords, and real estate funds have stepped in — with deep pockets, fast access to capital, and aggressive acquisition strategies.

They don’t need to live in the properties.

They don’t need to negotiate mortgage terms.

They don’t wait.

Instead, they buy entire apartment blocks, rows of houses, or land parcels before private buyers even get a chance to bid.

This creates a silent distortion:

- Prices rise not because of natural demand, but because of financial power plays.

- Homes are no longer valued as places to live, but as assets to extract profit from.

- Neighborhoods are reshaped not by those who live in them, but by those who profit off them.

The everyday buyer — a teacher, a nurse, a young couple — enters the same market with a fraction of the means and none of the leverage. In this game, they’re not just outbid — they’re outmatched.

And so the ownership dream erodes further, not through personal failure, but through a system that favors capital over community, and speculation over stability.

4. Generational Fallout: From Owners to Permanent Renters

Young adults trapped in a cycle of renting without equity

For today’s younger generation, homeownership is no longer a milestone — it’s a mirage.

Even well-educated, full-time working adults are discovering that renting isn’t just a phase. It’s becoming a permanent condition.

They pay more each year.

They move more often.

They save less — not for lack of discipline, but because there is nothing left to save after rent, insurance, and rising living costs.

But here lies the deeper tragedy:

Every month’s rent builds no equity, secures no future, and creates no asset. It only guarantees continued dependency.

This is a fundamental shift in the economic trajectory of Europe’s middle class.

Where previous generations could expect to own property by their 30s or 40s, many of today’s young adults will remain lifelong renters, at the mercy of the market, with little long-term security.

The effect is not only financial, but psychological:

- A sense of rootlessness.

- The delay or abandonment of family formation.

- A growing perception that working hard is no longer enough.

The promise once offered by a stable job and a modest lifestyle — a home of your own, a place to belong — is collapsing. And with it, a pillar of European social stability is quietly being dismantled.

No inheritance, no security – intergenerational unfairness

For many young Europeans, the only realistic path to homeownership is no longer through work — but through inheritance.

Yet this path is narrow, uneven, and increasingly unjust.

Those whose families own property may one day inherit a foothold in stability.

But millions of others — children of renters, migrants, or low-income workers — face a future with no cushion, no asset, and no security.

This is more than an economic imbalance.

It’s a structural reproduction of inequality, passed from one generation to the next.

The consequences are stark:

- A divided society between those who own and those who pay forever.

- Growing resentment, as hard work fails to translate into progress.

- A quiet erosion of social mobility — and with it, the promise of democracy itself.

Europe once prided itself on opportunity and fairness.

But if access to housing is now a matter of family fortune, not effort or merit, then something has gone deeply wrong.

What we are witnessing is not a housing market malfunction —

it is a generational betrayal.

Psychological toll: instability as the new normal

The housing crisis is not just material — it’s psychological.

When people are forced to move every few years, when rents consume half their income, when the future is one long lease with no security — something deeper begins to erode.

Instability becomes the norm.

Plans are put on hold.

Families are delayed.

Roots are never grown.

A generation that cannot picture owning a home often cannot imagine settling down at all.

The constant precarity breeds anxiety, burnout, and a sense of quiet despair.

Children grow up without the safety of a permanent home.

Young couples postpone having kids, unsure if they’ll be able to afford a place next year.

Elderly renters live in fear of eviction.

This isn’t just a housing issue — it’s a crisis of belonging.

And over time, the psychological toll becomes political:

- Disillusionment with institutions that offer no answers.

- Distrust of systems that reward speculation over shelter.

- A quiet rage that simmers beneath society’s surface.

Without stability, there can be no well-being.

And without well-being, democracy itself becomes brittle.

5. Social Consequences of Housing Injustice

Disconnection from neighborhoods and community

Housing is not just about walls and roofs — it’s about belonging.

When people are constantly displaced, or priced out of their familiar streets, they lose more than a home. They lose their community, their networks, their emotional anchors.

Neighborhoods become temporary spaces — filled with strangers, not neighbors.

Local traditions fade. Corner stores vanish. Parks grow quiet.

When a street changes hands every few years — when the faces change faster than the seasons — there’s no space left for long-term trust or collective identity.

People stop greeting each other.

Children lose playmates.

Elderly residents grow isolated.

This erosion of community fabric is slow, silent — but devastating.

And it hits hardest in places where community was once the only safety net.

Because when the system fails, people used to turn to each other.

But if everyone’s gone, who is left to turn to?

Displacement doesn’t just scatter people.

It shatters connection — and with it, the very glue that holds society together.

Urban flight, gentrification, and forced periphery migration

What was once a natural process — people moving to where life is better — has turned into a forced exodus.

In major cities across Europe, neighborhoods once home to working families are now playgrounds for the wealthy.

Gentrification isn’t about revitalization anymore — it’s about replacement.

Artists open cafés. Investors follow.

Then come the luxury renovations.

And soon, those who built the neighborhood can no longer afford to live there.

They don’t leave by choice.

They are priced out.

Or pushed out by rent hikes, fake renovations, and the slow squeeze of exclusion.

The result?

A wave of urban flight — not driven by opportunity, but by survival.

Families are pushed to the edges of cities, to places poorly connected, underfunded, and neglected.

Children spend hours commuting.

Jobs are harder to reach.

Elderly care becomes distant.

This forced migration fractures social ties and economic chances alike.

And the cities?

They become hollow — vibrant only on the surface, sterile underneath.

A place of privilege at the core, surrounded by rings of forgotten lives.

Europe is not building inclusive cities.

It is building divided landscapes, one eviction at a time.

Political radicalization born from hopelessness

When people lose their homes, they don’t just lose a roof.

They lose stability, dignity, and a place in society.

And when this loss becomes widespread — when thousands experience the same quiet betrayal —

anger begins to grow.

Not loud at first.

But steady.

Deep.

A system that protects property more than people breeds resentment.

A democracy that speaks of fairness while millions are priced out of their lives loses credibility.

Hopelessness is not passive.

It turns into searching — for answers, for someone to blame, for someone who listens.

And too often, the loudest voices waiting in that vacuum are the most extreme.

This is how housing injustice fuels radicalization.

When people feel that lawful paths offer no justice, they turn to unlawful ones.

When centrist parties offer only silence, they look to those who scream.

Left, right — it doesn’t matter.

It’s not ideology that spreads first.

It’s disillusionment.

The rise of political extremes across Europe is not happening in a vacuum.

It is rooted in the lived experience of being abandoned.

Housing is not just economics.

It is a pillar of social peace.

And when that pillar crumbles, the whole structure begins to shake.

6. A Structural Perspective: Housing as Infrastructure

Homes are not commodities – they’re foundations of stability

For too long, housing has been treated like any other market asset —

a vehicle for profit, a line in a portfolio, a tradeable commodity.

But a home is not a commodity.

It is the place where children grow up, where families take root,

where elderly people find safety and memory.

It is where life happens — quietly, daily, meaningfully.

To treat homes like stocks or bonds is to confuse shelter with speculation.

And when housing becomes just another arena for global capital,

people become collateral.

Stability — emotional, social, economic — begins at home.

When housing is secure, people can plan, work, invest in their communities.

When it is precarious, all other forms of stability begin to erode.

A home is not simply where we live.

It is what allows us to live with dignity.

That is why housing policy cannot be left to the market alone.

It must be viewed as infrastructure — just like roads, water, or power.

A society that understands this invests not only in walls and roofs,

but in resilience, cohesion, and peace.

Resilience needs decentralization and diversity in ownership

In nature, resilience comes from diversity —

different roots, different seeds, different pathways.

The same is true for housing.

A stable, just society cannot rely on a few large landlords

or global investment funds to provide shelter for millions.

When ownership is centralized, risk becomes systemic.

A single downturn, a policy shift, a profit-driven decision —

and thousands lose their homes.

Real resilience requires a mosaic of ownership:

- Individuals who live in what they own.

- Cooperatives that share responsibility and costs.

- Municipalities that protect public housing stock.

- Trusts and foundations that serve community goals, not quarterly returns.

When homes are held by many — with different motives and time horizons —

housing systems become less fragile, more humane, and more adaptable.

Diversity in ownership also creates diversity in living:

not just luxury apartments or soulless box housing,

but a mix of forms, functions, and futures.

If we want cities that breathe and villages that survive,

we need to decentralize power over housing —

and return it to the people who live inside the walls.

Speculation must be separated from shelter

A home should be a place to live —

not a slot machine for global capital.

Yet in today’s economy, housing has been reduced

to an asset class, a speculative tool, a profit engine.

Apartments sit empty while people sleep on the streets.

Prices rise not because demand increases,

but because someone far away bets on your city’s growth.

Speculation warps everything:

– It drives up costs for buyers and renters alike.

– It incentivizes vacancy over occupancy.

– It pushes communities out in favor of short-term gain.

But shelter is not a luxury.

It is a basic human need — as vital as food, water, and air.

To treat it like a stock portfolio

is to deny its most essential function:

stability, safety, and belonging.

Policies must draw a hard line:

If you don’t live in it, you don’t profit from it.

We need legal, fiscal, and cultural tools

that reclaim housing as infrastructure —

not investment.

Only then can we restore balance

between the right to profit and the right to exist.

7. Toward a Fair Housing Future

Stronger renter protections across Europe

Renting shouldn’t feel like walking a tightrope.

Yet for millions across Europe,

one missed paycheck,

one landlord’s whim,

or one renovation notice

can mean losing everything.

This is not personal failure.

It is a political one.

Tenant protections are fragmented, outdated, or riddled with loopholes.

In some countries, rent caps are missing.

In others, eviction notices arrive with little warning.

Corporate landlords exploit legal grey zones,

and local governments often look away.

A fair Europe must mean:

– Transparent rental contracts

– Predictable, affordable rent increases

– Restrictions on no-fault evictions

– Legal aid for tenants facing harassment or displacement

– National databases to monitor rent trends and abuses

But more than that, we need a cultural shift:

Renting must no longer be seen as second-class living.

The renter is not “just passing through” —

they are part of the social fabric.

A home is a home —

whether you own it or not.

Public investment in non-profit and cooperative housing

Markets alone cannot solve a housing crisis they helped create.

For decades, public housing was cut, privatized, or neglected —

all in the name of efficiency and growth.

But what followed was not efficiency,

only exclusion.

Now, with millions struggling to afford basic shelter,

governments must return to their role as guarantors of dignity.

Non-profit and cooperative housing models are not charity —

they are infrastructure.

They stabilize markets, prevent speculation,

and create long-term, affordable homes

immune to investor whims.

Europe needs a housing renaissance built on:

– Direct public investment in construction and land acquisition

– Support for housing cooperatives where residents co-own and govern

– Land trusts that remove property from speculation permanently

– Long-term affordability clauses to stop the sell-off of public assets

These models already exist — in Vienna, in Zurich, in parts of Scandinavia.

They work. They scale. They protect.

It’s time to stop treating affordable housing

as a burden on public budgets

and start seeing it as an investment

in the social contract itself.

Incentives for local ownership, disincentives for speculation

If we want homes to serve people,

we must change the rules that reward those who treat them like chips in a casino.

Today, the housing market favors the largest wallets,

not the deepest roots.

Locals are outbid.

Communities are hollowed out.

Profit is extracted — but nothing is given back.

We need to reverse this logic.

Governments across Europe can act decisively by:

– Offering tax breaks for residents who buy and live in their homes

– Supporting intergenerational transfers within families and communities

– Creating purchase-right programs for tenants when buildings are sold

– Heavily taxing vacant properties and short-term speculation

– Restricting bulk purchases by investment funds and foreign entities

– Encouraging local financing options through credit unions and public banks

A house should be a home — not a hedge fund’s asset.

By actively shaping the market,

we can prioritize stability over volatility,

presence over profit.

The future of our cities depends on who gets to stay.

Land and housing policy as a pillar of democratic health

Democracy does not live in institutions alone.

It lives in the everyday — in people’s ability to stay rooted,

build a life, raise a family, care for others,

and feel safe in their own home.

When housing becomes unstable,

so does the social contract.

When land is owned by absentee investors

and policy is written for markets, not for people,

citizens lose trust — and eventually, their voice.

A just land and housing policy is not just economic. It’s civic.

We need a Europe where:

– Land serves the public good, not private hoarding

– Urban and rural planning empowers communities, not only developers

– Access to affordable housing is seen as a right, not a reward

– People have a stake — literally — in the future of where they live

The health of a democracy depends on whether people believe

that the ground they walk on belongs — even in part — to them.

We do not need to start from scratch.

We need the courage to remember what a home means.

8. Call to Action: Housing Must Be Reclaimed

Europe needs a housing reset – urgently

What’s happening is not an accident.

It’s the result of decades of policies that treated housing

as an investment vehicle instead of a basic need.

Markets were liberalized, protections were eroded,

and the language of “efficiency” replaced that of justice.

Now, the signs are everywhere:

– Entire generations locked out of ownership

– Elderly tenants pushed from their homes

– Communities hollowed out by speculation

– Public land sold off like surplus stock

This is not sustainable. Not morally. Not socially. Not economically.

Europe needs a housing reset — not another decade of delay.

That means:

- Recognizing housing as critical infrastructure, not private luxury

- Ensuring stable, fair, and local ownership models

- Confronting predatory investment practices head-on

- Building a legal framework that puts people before profit

The housing crisis is not just a policy failure.

It is a moral failure.

But it can be reversed — if we act now, with clarity and conviction.

Citizens, policymakers, and movements must realign priorities

Solving the housing crisis is not just about passing new laws.

It’s about resetting the compass — socially, politically, and culturally.

We must ask:

What kind of society do we want to live in?

One where shelter is secure, or one where it’s a gamble?

Right now, many policymakers still treat rising property prices as success.

Citizens are told to “invest smarter” or “move further out.”

Movements get fragmented, siloed, or ignored.

But the truth is clear:

We cannot fix housing without realigning our values.

That means:

- Citizens recognizing that this is not just a personal struggle, but a collective one — and making their voices heard.

- Policymakers admitting that deregulation and market worship have failed, and daring to challenge entrenched financial interests.

- Movements coming together — across class, age, and region — to demand housing as a human right, not a profit stream.

This isn’t just policy work.

It’s cultural work.

It’s moral work.

And it starts with one simple shift:

Putting people — not markets — at the center of housing.

Reclaim the right to dwell – with dignity, stability, and voice

At its core, the housing crisis is a crisis of belonging.

To dwell is not just to inhabit space.

It is to exist with dignity,

to live with stability,

and to be heard — with a voice that matters.

When people are uprooted again and again,

when rent devours half their income,

when a home is reduced to a financial product —

something profound is lost.

A society that cannot guarantee shelter

cannot call itself just.

And a democracy that allows millions to live

in fear of eviction or exclusion

forfeits part of its soul.

We must reclaim the right to dwell —

not as a luxury,

but as the foundation of freedom.

Because without a stable place to stand,

no one can rise.

If you’d like to explore these ideas further, share your perspective, or contribute something –

the Aurora team can be reached at: ✉️ mail@project-aurora.eu