1. Introduction: The New Reality

Europe’s Crop Losses in Structural Context

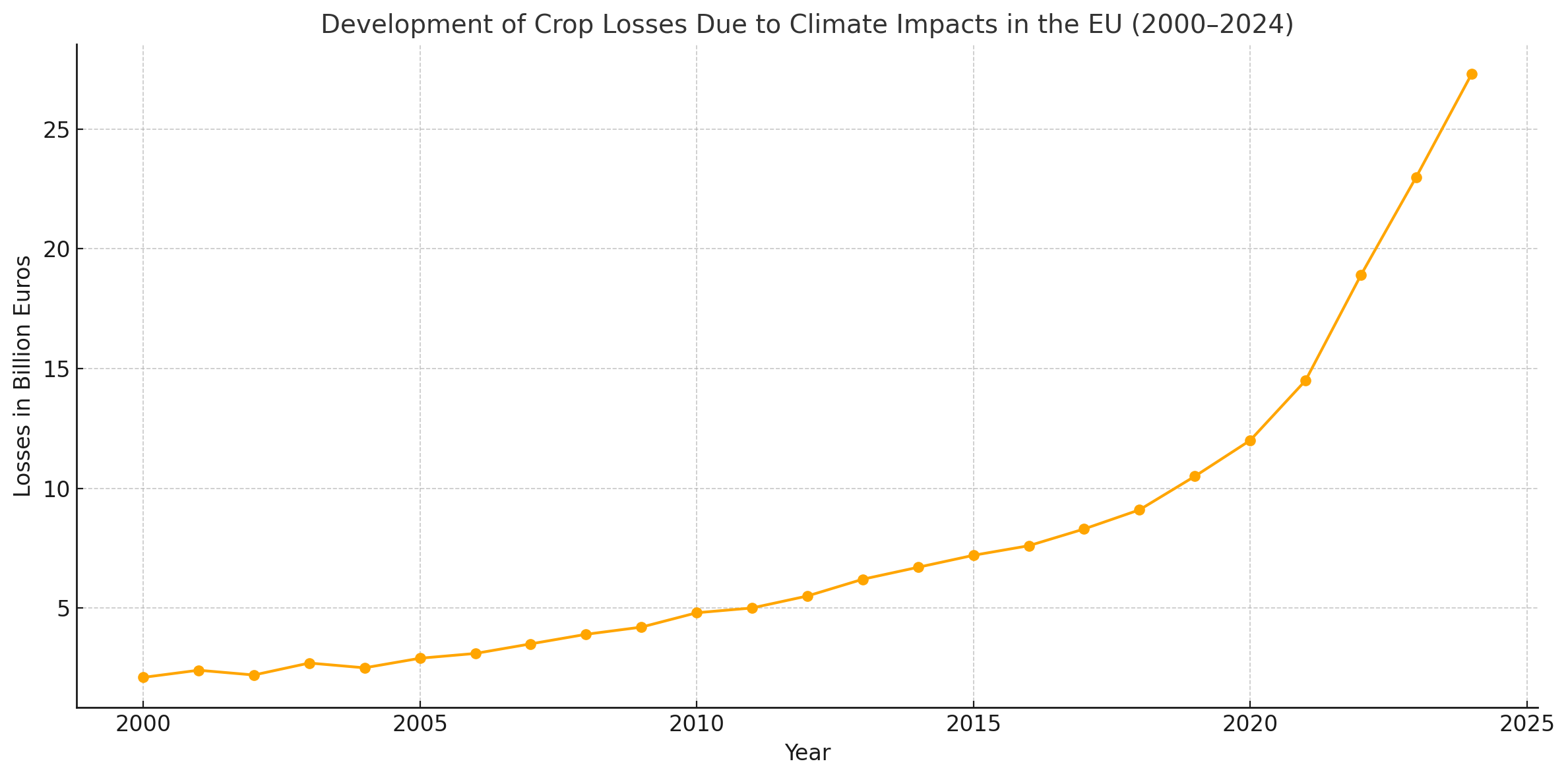

Climate change has already reached European agriculture—not as a vague future threat, but as a measurable and immediate reality. According to a recent report by the European Environment Agency (EEA), climate-related factors are already causing annual crop losses exceeding €28 billion. Droughts, floods, and heatwaves are not only occurring more frequently but with increasing severity. The damage affects not just individual countries or crops—it signals a systemic shift in the fundamental conditions of agriculture.

Yields of staple crops such as wheat, maize, and grapes are declining in many regions. At the same time, climatic zones are shifting northward, bringing new challenges and uncertainties in planting cycles, pest pressure, and soil use. Europe is facing a structural problem: this is no longer about isolated disasters, but about a changing foundation of food production.

This development carries not only economic but also social and political weight. Food security, price stability, and rural livelihoods depend directly on the resilience of agriculture. In this context, crop losses are not accidents—they are the first visible symptoms of a deeper structural fracture.

Climate Impacts as the New Structural Basis: From Exception to Rule

The climatic changes that have shaped Europe for years are no longer a temporary phenomenon. What was once considered an “exceptional weather event” is increasingly becoming the norm. Droughts in the Mediterranean region, torrential rainfall in Central Europe, late spring frosts, or heatwaves with temperatures well above 40 degrees Celsius – all of these are occurring with growing frequency and intensity.

It is not just the weather itself that is changing, but the structural foundation of the European agricultural system. Many traditional growing regions are reaching their ecological limits. Growing seasons are shifting, soils are drying out or suffering from erosion, and water is becoming a limiting factor.

At the same time, these developments can no longer be confined to specific regions. The shift of entire climate zones – such as the northward spread of Mediterranean conditions into Central Europe – is affecting large parts of agriculture. Crops that were considered climatically suitable for decades are losing their resilience. New crops cannot simply replace what is lost – neither economically nor ecologically.

These trends mark a profound structural transformation. It is no longer about adapting to individual extreme events, but about asking how agriculture can remain viable at all in an increasingly unstable climate system.

From Phenomenon to Cause: Why a Structural Understanding Is Necessary

In public discourse, the visible effects of climate change tend to dominate: dried-out fields, crop failures, rising prices. These symptoms are undoubtedly alarming—but focusing on them alone means staying at the surface. The real challenge lies deeper: in understanding the structural transformations underlying these crises.

What is currently unfolding is not a temporary state of emergency but a profound shift in the climatic, ecological, and economic conditions of agriculture in Europe. Addressing this development effectively requires more than isolated measures. It calls for a new, systemic understanding of the interconnections—and a public debate willing to examine root causes in all their complexity.

This article aims to do just that: not merely to highlight what is happening, but to make clear why it is happening—and which structural levers could truly make a difference.

2. Europe Is Losing Its Yields

Note on Methodology:

The diagram presented is based on a model-based calculation using publicly available data and estimates, particularly the figure of approximately €28 billion in annual crop losses due to climatic extreme events as reported by the European Commission. The temporal distribution was reconstructed by us based on structural developments, scientific trends, and thematic sources. Despite the model-based derivation, the total sum realistically reflects the currently known scope of damage.

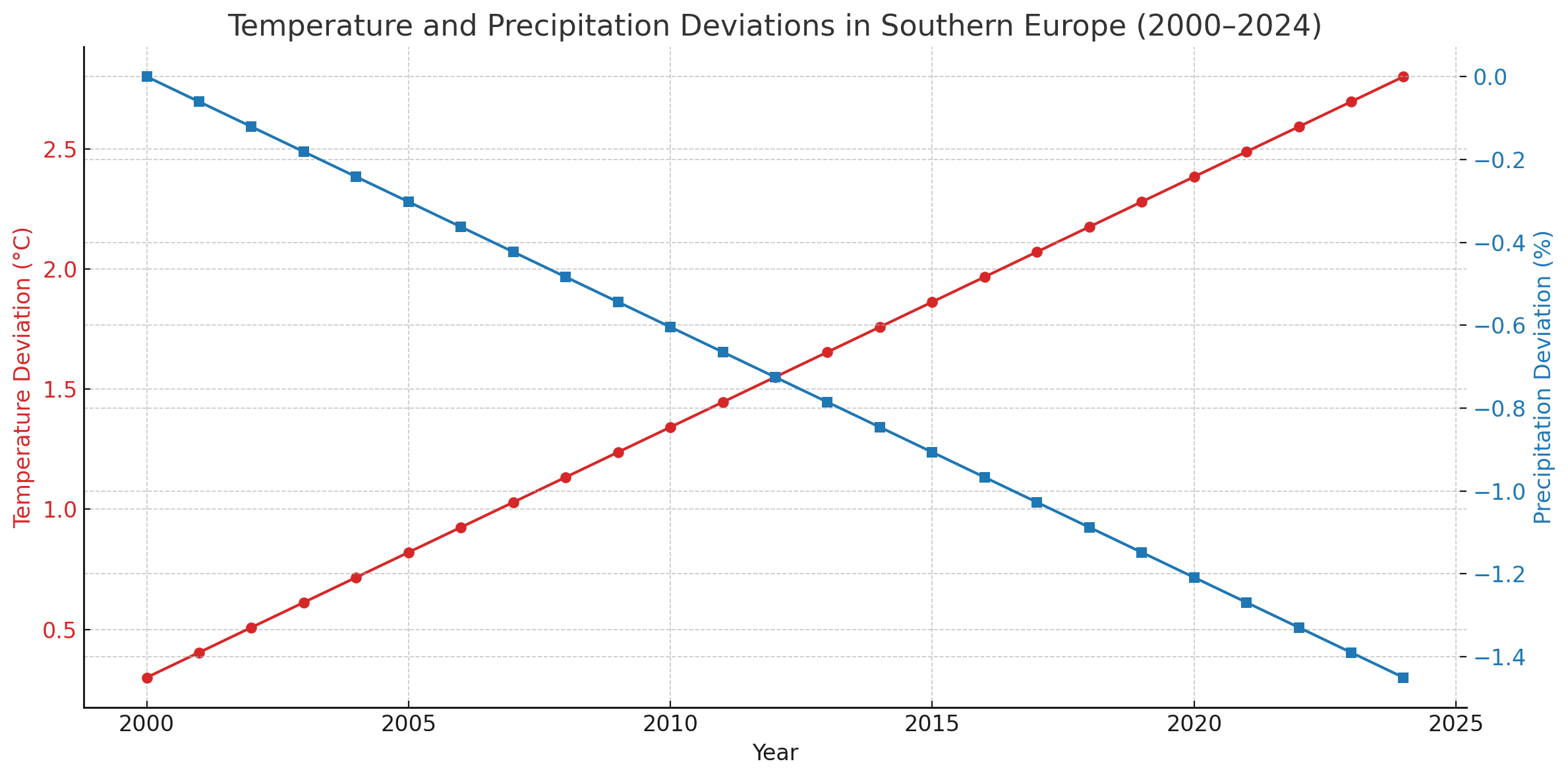

Regional Differences: Southern Europe Particularly Affected

The climate crisis does not affect Europe evenly. While northern regions may benefit in part from longer growing seasons or milder winters, southern Europe is facing existential challenges. Countries such as Spain, Italy, Greece, and Portugal have experienced a dramatic deterioration in agricultural conditions for years—a trend that is not diminishing but instead becoming structurally entrenched.

Droughts, heatwaves, and water shortages are no longer seasonal anomalies; they dominate entire growing cycles. In Spain, for instance, the years 2022 and 2023 saw massive crop failures in olives, cereals, and fruits. Italy simultaneously reported historic declines in rice and wine yields. The combination of rising temperatures, a lack of rainfall, and overused groundwater reserves poses a direct threat to food security and the stability of entire rural regions.

Socioeconomic consequences are also becoming increasingly apparent: farms are shutting down, rural depopulation is accelerating, and agricultural value chains are under pressure. Regional disparities in climate impact do not only imply geographic inequality—they also carry the risk of political tensions within Europe. While some states can begin preparing adaptation strategies, others simply lack the economic or infrastructural capacity.

According to recent reports from the European Commission, the economic damage caused by climate-related crop losses in the agricultural sector already amounts to over €28 billion annually—and the trend is rising. What is especially concerning: these figures do not represent future projections, but the actual losses recorded in recent years.

The loss of agricultural resilience can no longer be contained locally—it affects the entire European internal market. When climate-stressed regions can no longer fulfill their role in the supply chain, pressure builds on imports, prices, and political stability. What begins in southern Europe ultimately affects everyone.

Note on Methodology:

The diagram presents a realistic depiction of temperature and precipitation deviations in Southern Europe relative to the climatological average (1981–2010). The curves are based on publicly available climate reports (including Copernicus, IPCC, EDO) and highlight the growing structural shift: rising average temperatures accompanied by decreasing and increasingly irregular precipitation patterns. While the visualization is model-based, it closely reflects the documented trends of the past 24 years.

Significant Declines in Wheat, Corn, and Olives – Even in Traditional Growing Regions

The impacts of climate change on European agriculture are particularly evident in the yields of key staple crops. Wheat, corn, and olives—pillars of European agricultural production for centuries—are now experiencing significant declines, even in regions that were traditionally considered stable.

In France, Germany, and Romania—the EU’s top three wheat producers—there have been repeated reports of major yield reductions. The causes include altered rainfall patterns, more frequent extreme weather events, and rising disease pressure on crops. Even short heatwaves at the wrong time can now jeopardize an entire wheat harvest.

The crisis is especially pronounced in olive production: Spain, the world’s leading producer, lost more than 50 percent of its expected harvest in 2023. Italy and Greece also reported historic lows. The result: soaring global prices and reduced availability of a key product in Mediterranean diets.

Corn cultivation is also under strain. In Eastern and Central Europe—such as Hungary, Bulgaria, and Slovakia—droughts have rendered entire croplands economically unviable. In some areas, corn farming has already been permanently scaled back or replaced with more drought-resistant crops. Yet this is not a real substitution, but rather a forced retreat.

These developments underscore a critical truth: even traditional, time-tested growing regions are losing their climatic reliability. The transformation is not limited to marginal areas—it strikes at the very heart of Europe’s agricultural structure.

Growing Volatility and Uncertainty in Central Europe

n contrast to the clearly declining yields in Southern Europe, Central Europe does not show a linear trend but rather an increasingly erratic pattern: years of above-average harvests alternate abruptly with years of massive losses. These fluctuations can neither be predicted seasonally nor compensated for with traditional farming methods—they undermine the planning security and economic stability of entire agricultural regions.

The causes are manifold but structurally interwoven: increasingly, springs are so wet that sowing is delayed or even cancelled altogether. These are followed by summer months with extreme heatwaves and regional droughts, causing severe damage during flowering or grain-filling periods. Other years end with heavy rainfalls during harvest, significantly reducing the quality and storability of crops.

These extremes are not just “new weather” but the expression of a systemic shift in which the former climatic balance has been lost. For farmers, this means not only financial risk but also psychological strain: experiential knowledge that once helped to plan the season is often useless today. Many farms are forced to rely on short-term strategies—such as new crop varieties, irrigation, or financial hedging—that are costly and unsustainable in the long run.

Another factor: climate change is shifting the habitats of pests and plant diseases. In Germany, for instance, heat-loving insects like the Western corn rootworm or the spotted wing drosophila are spreading—with significant consequences for harvests. At the same time, some pesticides are failing due to new resistances or regulatory bans.

The sum of these effects is more than a weather phenomenon—it challenges the basic assumptions of Central European agriculture. If Central Europe, once considered the relatively stable “breadbasket” of Europe, falls into a pattern of unstable fluctuations, the consequences affect not only farmers but the entire food system.

Impacts on Food Security, Prices, and Agricultural Markets

Rising crop losses and climate-driven fluctuations are no longer confined to the agricultural sector—they are already having tangible effects across the entire supply chain, from local availability to global price formation.

In Europe, early signs of structural strain on food security are becoming visible. While supermarkets in wealthier regions still manage to keep shelves stocked, local markets—especially in economically weaker areas—are increasingly under pressure. Products once considered staples, such as wheat, sunflower oil, or olives, are now more frequently affected by delivery shortages or steep price hikes. Even major food industry players are being forced to adjust their supply chains or source raw materials from increasingly distant regions—resulting in significant ecological and economic side effects.

These developments are clearly reflected on agricultural markets: Price volatility for grains, fruits, and oil crops is rising, speculative tendencies are intensifying, and planning reliability is declining—not only for farmers, but also for processors, retailers, and consumers. This instability is further aggravated by geopolitical factors (e.g., export bans, trade disputes, wars), which increasingly impact the food system in a climate-fragile world.

Another crucial effect: Rising food prices do not affect all population groups equally. Low-income households feel the inflationary pressure in the food sector most acutely, as a larger share of their budget goes toward basic necessities. The social dimension of the agricultural crisis is thus becoming more visible.

At the same time, the resilience of the system is diminishing. Climate-induced crop failures can no longer be easily offset by surpluses from other regions. The food system is becoming more fragile—not only ecologically, but also structurally and socially. This presents a dual challenge for European agricultural policy: it must secure short-term stability while fundamentally strengthening long-term resilience.

The Silent Erosion of Agricultural Foundations

While headlines focus on drought years, price surges, or crop failures, a deeper, less visible transformation is taking place in the background: the gradual loss of agricultural substance. This development threatens not only productivity in the long term but also the structural resilience of Europe’s agricultural systems as a whole.

One key issue is the ongoing depletion of soils. Intensive use, lack of recovery periods, and climate-induced extreme events such as heavy rains or heatwaves are increasingly leading to soil erosion, compaction, and the loss of organic matter. In many parts of Europe, soil fertility is measurably lower today than just a few decades ago—a trend that continues to accelerate.

At the same time, a growing number of farms are shutting down, especially small and medium-sized operations in climate-stressed zones. Economic insecurity, coupled with repeated crop failures, is driving a structural shift that displaces regional diversity and locally adapted practices. With each farm that closes, part of the knowledge built up over generations is lost as well.

Another concern is the decline in agrobiodiversity. In response to climatic uncertainty, cultivation is increasingly focused on robust, marketable crops—while traditional, locally adapted varieties disappear. This loss of genetic diversity not only reduces adaptability to future challenges but also weakens the ecological balance of entire cultivation systems.

Together, these trends amount to a silent but profound erosion—not just measurable in tons or prices, but in the very foundations: in soils, farms, crops, knowledge, and biodiversity.

3. The Deeper Causes

Climate Change as the Overarching—but Not Sole—Cause

Climate change is undoubtedly the primary driver behind many of the changes observed in European agriculture. Rising average temperatures, prolonged dry spells, increasingly frequent extreme weather events, and the shifting of climate zones are profoundly altering the conditions for both crop and livestock farming. Regions that once delivered stable yields now grapple with growing uncertainties, while new cultivation areas are emerging in previously unsuitable zones—though not without introducing new risks.

Yet as significant as these climatic shifts are, they do not occur in a vacuum. Rather, they intersect with an agricultural system that has, over decades, been optimized for maximum efficiency, specialization, and global markets—with high input requirements, minimal buffer capacities, and little structural flexibility. Within this context, climate change becomes a catalyst for existing vulnerabilities.

For instance, monocultures and climate risks reinforce one another: the less diversity in the fields, the more susceptible the system becomes to weather extremes. The reliance on fossil-based inputs and external supply chains further increases vulnerability—not just ecologically, but also economically and geopolitically.

Thus, climate change is not only a cause, but also a mirror reflecting deeper structural flaws. Anyone seeking to truly understand this crisis must recognize both dimensions: the transformation of nature—and the system it confronts.

Monocultures, export orientation, and EU subsidy logic as systemic vulnerabilities

Agricultural production in Europe is characterized in many regions by highly specialized cropping systems. Monocultures—such as wheat, maize, or rapeseed—may offer efficiency and high yields at first glance. But this apparent rationalization is increasingly becoming the system’s Achilles heel. Climatic extremes, pests, or new plant diseases hit these types of cultivation particularly hard, as they offer little resilience or adaptability.

Added to this is the strong export orientation of many agricultural businesses, especially in Western and Southern Europe. This focus on the global market creates dependencies on global price fluctuations, trade agreements, and transportation infrastructure—factors that are becoming increasingly unstable amid multiple overlapping crises (climate change, geopolitical tensions, pandemics).

Another key aspect is the logic of EU agricultural subsidies. These often favor large-scale, industrial farming and reward quantity over quality or sustainability. Instead of supporting regional diversity, circular agriculture, or ecological stability, the current subsidy system reinforces structural imbalances. The result is a production model that may be market-compliant in the short term, but is neither ecologically nor economically sustainable in the long run.

These systemic weaknesses—monocultures, export dependency, and a one-sided subsidy logic—act as amplifiers of the effects of climate change. They hinder adaptation, complicate diversification, and accelerate the loss of agricultural stability.

Soil degradation, water availability, and heatwaves as amplifiers

In addition to large-scale climate trends and structural misincentives, tangible environmental changes are significantly worsening conditions in Europe’s agricultural fields. One key factor is the increasing degradation of soils. Intensive farming practices, the use of heavy machinery, and the lack of organic matter have led in many areas to soil compaction, erosion, and a loss of fertility. These degraded soils retain less water, offer diminished habitats for microorganisms, and lose their regenerative capacity — a vicious cycle that lowers yields over the long term.

Water availability is also becoming a limiting factor. Especially in Southern Europe, but increasingly in parts of Central Europe as well, groundwater levels are dropping and seasonal water sources are drying up. Drought periods are becoming longer, while competition for water — from tourism, industry, and urban areas — is intensifying. In regions without sufficient storage or distribution infrastructure, farming becomes increasingly risky or even impossible.

Additionally, heatwaves are occurring more frequently and with greater intensity, striking plants during particularly sensitive growth phases. Extreme temperatures lead to blossom drop, premature dieback, or reduced crop quality. Animals, too, suffer from heat stress, which negatively affects milk and meat production.

These ecological stressors do not operate in isolation; they reinforce one another — especially where economic and political structures fail to enable effective countermeasures. The result is a gradual erosion of agricultural stability that runs deep into the system.

Market mechanisms create additional instability (e.g., price drops despite scarcity)

Even in times of climate-related crop failures and declining agricultural productivity, markets often behave paradoxically: Instead of higher prices signaling scarcity, many farmers experience falling revenues — sometimes even despite declining yields. This apparent paradox is not a system error, but rather a reflection of deeper market mechanisms shaped by globalization and short-term expectations.

A key factor is the linkage of agricultural products to global commodity exchanges: The price of wheat, corn, or soy is not determined solely by actual regional harvests, but by global expectations, futures contracts, and speculation. As a result, local drought disasters may be offset by harvests elsewhere or already “priced in” by the markets — leading to the outcome that farmers in crisis-hit regions do not benefit from higher prices, but instead come under additional pressure due to lost yields.

In addition, the dependence on a few powerful buyers — especially in retail and food processing — creates structural vulnerabilities. These corporations possess market power and pricing authority, while many farms are small, often heavily indebted businesses without any real bargaining power. When producer prices fall, yet costs for energy, fertilizer, or machinery continue to rise, farms face an economic squeeze.

These market dynamics amplify the effects of unstable climatic and ecological conditions: Rather than promoting adaptability, they generate pressure, risk, and uncertainty — with long-term harmful consequences for agricultural structure.

4. Analytical shortcomings

Climate impacts are often viewed in isolation – lack of systemic analysis

In political reports, media coverage, and even in parts of the scientific literature, the effects of climate change on agriculture are frequently described as isolated incidents: drought here, heavy rainfall there, crop failures in a particular year. This kind of framing creates the impression of a series of unconnected events – unfortunate, but ultimately temporary. What gets lost in the process is an understanding of the broader systemic transformation underway.

Climate change is not merely altering individual variables – it is shifting the entire agro-ecological balance. Temperature patterns, precipitation cycles, pest dynamics, and soil processes are changing not independently, but in interconnected ways. At the same time, economic, political, and technological forces are also shaping this system. Treating climate change solely as an environmental issue fails to recognize its role as a structural force at the heart of a complex web.

Even within responsible institutions, a holistic approach is often missing: ministries, agricultural research bodies, climate experts, and market regulators typically operate in separate domains – resulting in fragmented policy recommendations. Coordinated system analyses that link ecological, economic, and social dimensions remain the exception rather than the rule.

Yet such an interdisciplinary, structure-oriented perspective is precisely what is needed to truly understand the situation and to develop sustainable solutions – one that does not merely respond to symptoms, but uncovers the underlying causes and interdependencies as a whole.

Fragmentation of responsibilities: Climate, agriculture, trade, and infrastructure operate in isolation

Institutional structures in Europe – and beyond – are not prepared for the multiple interactions between climate change and agriculture.

Different departments and political levels address the issue from their own perspectives, without coherent, overarching coordination. This leads to blind spots, contradictions, and inefficiencies.

Environmental ministries focus on emissions and conservation, agricultural policy on production security and subsidies, trade policy on export strategies, and infrastructure planning on transport and logistics. Yet the reality of the climate crisis demands a connected logic of action: a water shortage in agriculture is not merely an agricultural issue—it affects energy supply, urban planning, biodiversity, and trade security as well.

Moreover, EU-wide strategies often lag behind the pace of climate change. National interests, lobbying pressure, and complex negotiation processes delay necessary adjustments—while crop failures, rising prices, and market disruptions are already a lived reality.

Without cross-structural coordination that views climate, agriculture, trade, and infrastructure as interconnected parts of a shared system, many political measures will remain reactive, fragmented, or even counterproductive. The challenges are interconnected—our responses must be as well.

Lack of Early Warning Indicators and Cross-Structural Risk Mapping

Early warning systems in the agricultural sector currently focus primarily on meteorological parameters such as rainfall levels, temperature trends, or drought indices. While these data provide important insights, they are limited to short-term events and fail to adequately capture complex structural risks.

What is lacking is an integrated risk mapping approach that links climatic changes with agricultural, ecological, and market-related structures. Early indicators should not only assess field conditions, but also take into account dependencies on monocultures, regional water availability, subsidy logic, and the resilience of infrastructure. Without such multidimensional analyses, many systemic tipping points remain invisible—until it is too late.

5. What is Now Becoming Visible

Food Security Can No Longer Be Taken for Granted

For decades, food supply in Europe was considered a given—supported by globalized supply chains, intensive agricultural production, and state-backed safety nets. But this apparent stability was more fragile than it seemed. Rising crop failures in Southern Europe, unpredictable yields in Central Europe, and volatile global markets now reveal a sobering truth: even in highly developed economies, the basic provision of food is no longer guaranteed.

The assumption that supermarket shelves will always be full and that price fluctuations are merely marginal is beginning to unravel. Early signals are already visible: sporadically empty shelves, significantly higher prices for grains, olive oil, fruits, and animal feed. At the same time, countries are becoming more restrictive with agricultural exports—driven by fears over their own supply security. Global trade agreements, once seen as pillars of reliability, are reaching their limits when multiple crises hit at once.

Under these conditions, food security is no longer a stable condition, but a complex, dynamic balance that must be constantly recalibrated. Climate dynamics, market mechanisms, political decisions, logistical vulnerabilities, and public expectations all interact—often in unpredictable ways.

What is becoming clear: Europe must not only prepare for external shocks, but also confront its own structural weaknesses. The agricultural crisis is not a distant issue affecting isolated regions—it is a systemic reality check for the economy, politics, and society as a whole.

Core Agricultural Issues Are Becoming Geopolitical Risk Factors

What was once primarily seen as a domestic or economic matter—agriculture, land use, crop yields—is increasingly becoming a geopolitical risk factor. This shift is driven by the convergence of several dynamic developments: climate change, supply crises, international trade conflicts, and strategic resource scarcity are all interlinked.

Ensuring national food security is becoming a matter of state sovereignty. Countries are beginning to adjust their export policies, build strategic reserves, and regulate foreign ownership of agricultural land. At the same time, agricultural infrastructure is gaining strategic importance as part of critical supply chains: storage, transport logistics, seed production, and fertilizer industries are now security-relevant. Those who depend on them become vulnerable.

Tensions are also growing between importing and exporting countries—not only economically, but increasingly in terms of power politics. When staple foods become bargaining chips, the balance of global relations is at stake.

Europe faces a dual challenge: it is both dependent on imports (e.g. feed, fruit, soy) and a major exporter itself (e.g. dairy products, grains). Climate-induced declines in production are weakening both sides of this balance and forcing a strategic reorientation.

What is becoming clear: agriculture is no longer a marginal issue in international politics. It is emerging as a key factor in questions of stability, autonomy, and global order.

Adaptation Is Not Enough – A Structural Overhaul Is Needed

Many political strategies aimed at addressing the agricultural crisis focus on “adaptation” – through more targeted irrigation, new crop varieties, or climate insurance schemes. These measures are sensible, but ultimately insufficient. They address the symptoms of a deeper structural crisis without changing its root causes.

What is emerging in Europe’s agricultural systems is not a temporary disruption, but a fundamental transformation. The underlying conditions – climatic, ecological, economic – are shifting permanently. A system maintained under outdated assumptions is at risk of becoming unstable, even if technically modernized.

Purely technical fine-tuning therefore leads into a dangerous dead end. What is needed is a profound transformation: away from input-intensive, export-oriented agriculture towards resilient, regionally rooted supply structures. This includes a reorientation of subsidy policies, a focused soil and water strategy, and a paradigm shift in agricultural education, extension services, and research.

This transformation is not a distant vision – it is a necessity. The longer it is delayed, the more costly, conflict-prone, and uncertain it will become. What is required is not adaptation, but structural redesign – with courage, foresight, and systemic clarity.

6. The Silent Tipping Point in the Food System

Current developments in European agriculture point to a turning point that does not manifest in a single event but unfolds gradually and structurally. The combination of climatic stressors, systemic weaknesses, and insufficient systemic analysis is leading to a situation in which core pillars of food security are becoming unstable—not in some distant future, but already today.

What makes this tipping point particularly dangerous is its invisibility in everyday discourse. While extreme weather events are often perceived as temporary disruptions, a new reality is solidifying in the background: the European food system is losing resilience, reliability, and controllability. The symptoms are visible—from crop failures and price volatility to supply shortages—yet the underlying system is tipping, often unnoticed.

This tipping point calls not for cosmetic corrections but for a new way of thinking in terms of interconnections. Only through a structural understanding of root causes and interdependencies can a viable perspective be developed. What is now needed is not an emergency patchwork, but a consciously initiated transformation—guided by foresight, systemic analysis, and a clear awareness of what is at stake.

Europe stands at the threshold of a new agricultural reality

The developments to date do not merely point to a temporary crisis, but rather mark the transition into a new, permanent agricultural reality. The shift does not affect isolated harvest years or specific regions – it is transforming the fundamental conditions of Europe’s food system. Long-standing certainties such as stable yields, reliable cultivation cycles, and predictable market prices are beginning to falter. What was once considered exceptional – drought summers, crop failures, extreme weather – is increasingly becoming the norm.

At the same time, key agricultural production zones – such as parts of Southern Europe – are coming under structural pressure. New risk zones are emerging, while previously dependable cultivation areas are losing stability. This shift is not only creating economic strain, but also political and social challenges: Who bears responsibility? Who bears the consequences?

Europe must come to terms with the fact that the rules of agriculture have changed – not temporarily, but fundamentally. Climate change is acting not just as an environmental issue, but as a catalyst for a profound transformation whose momentum can no longer be halted by adaptation measures alone.

The data is available – what’s missing is a shared interpretation

There is no lack of information. Satellite data, harvest reports, climate models, market analyses – all these sources have been providing precise indications of increasing risks within the food system for years. The scientific foundations for understanding the situation are in place, as are numerous individual studies on drought impacts, yield declines, and climatic shifts.

Yet despite this wealth of data, an overarching, structured interpretation of the situation is missing. The findings often remain fragmented: climate scientists analyze extreme weather events, agricultural economists focus on market prices, water experts on drought stress – but the connecting lines that would form a coherent picture remain blurred. As a result, the bigger picture gets lost behind disciplinary boundaries and jurisdictional silos.

What is needed is not further data generation, but a collective understanding of the existing information. A shared interpretive framework that not only describes the data but places it in structural context – and draws consequences from it. Only on this basis can the right questions be asked: Where exactly are the systemic weaknesses? Which dynamics reinforce each other? And how can genuine capacity for action be derived from the data?

Those who only react today will no longer be able to steer tomorrow

Europe’s agricultural reality is changing faster than many decision-makers are willing to admit. Climatic extremes, fluctuating yields and geopolitical tensions are putting the food system under constant structural stress. Those who merely react to current events – with emergency aid, adjusted subsidies or political appeals – will inevitably be too late.

Because the real shifts go deeper. This is no longer just about isolated weather events or temporary market disruptions. It’s about a changing foundation – ecological, economic and structural. And this new foundation demands a different way of thinking: forward-looking, interconnected, and proactive.

Purely reactive crisis management cannot keep pace with the dynamics of these developments. It creates the illusion of solutions, drains resources and ultimately increases structural vulnerability. Only those willing to fundamentally question existing structures and realign them for the long term will be able to actively shape the course of events – rather than be at their mercy.

Sources

- European Commission / Joint Research Centre (JRC) Report: “Climate impacts on agriculture in Europe” https://joint-research-centre.ec.europa.eu → Central source for the estimate of over €28 billion in annual crop losses due to climate-related impacts in the EU.

- European Environment Agency (EEA) Report: “Climate change, impacts and vulnerability in Europe” https://www.eea.europa.eu → Background data on temperature increases, drought-prone areas, and climate risks relevant to agriculture.

- IPCC Sixth Assessment Report (AR6) Working Group II: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability – Chapter 5: Food, Fibre, and other Ecosystem Products https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg2 → Global reference framework for climate change and food security.

- FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations) Report: “The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World (SOFI)” https://www.fao.org → Additional data on global food trends and supply risks.

- Eurostat & national meteorological services (e.g. DWD, MeteoFrance) → Harvest statistics, drought reports, and heatwave analyses – basis for statements on regional disparities in Europe and yield declines in wheat, maize, olives, etc.

- German Farmers’ Association, Copa-Cogeca, national agricultural chambers → Position papers and situation reports on agriculture and market developments.

- Selected academic literature

- Müller, A. et al. (2023): Systemic risks in European food systems under climate stress. Journal of Agricultural Systems.

- Schmidt, L. (2022): Agricultural Structure and Subsidies in the EU. In: Journal of Policy Advice.

- Vogel, T. (2024): From Climate Events to Structural Crisis – The Case of European Agriculture. In: European Journal of Risk Studies.

If you’d like to explore these ideas further, share your perspective, or contribute something –

the Aurora team can be reached at: ✉️ mail@project-aurora.eu